I am currently reading Dussel’s Ethics of Liberation in the Age of Globalization and Exclusion. As is apparent by my last post, I have some unresolved dilemmas with Dussel’s thinking. Concretely, last post revolved around the Material Criterion which stated that:

Whoever acts humanly[1] always and necessarily has for the content of their act some mediation for the production, reproduction or self-responsible development of life of each human[2] subject in a life community [comunidad de vida], as material fulfillment of the cultural corporality necessities, with all of humanity as the ultimate reference [trans.].1

Again, what was problematized from such Criterion was not the formulation, but the implications of Dussel’s understanding of humanly. In sum, I argued that his association of the human with ‘superior’ cognitive capacities may lead to exclusions of certain humans who do not have those same cognitive capacities. Note that while Dussel builds his conception on the human for the Actor 1, his conception is consequential for the Actor 2, who would be the Other-in-mind when analyzing if an act has for its content the production, reproduction, etc., of this Other-in-mind. I want to clarify, however, that my point is that if we are to take the victims (as an analytical concept-category) seriously, then we ought to clearly define who can be a victim by another composition different from higher cognitive capacities. One could possibly take the Singer route and “abandon the idea of the equal value of all humans, replacing that with a more graduated view in which moral status depends on some aspects of cognitive ability, and that graduated view is applied both to humans and nonhumans”.2 My intuition is that such a view would wholeheartedly be rejected by Dussel and anyone invested in the Liberation Philosophy project (including me).

Where do we look then for a Dusselian supplement? Tracing back the steps taken by Dussel in his Ethics, I recognize his appreciation for Habermas’ subsuming of his critics (e.g. Rawls and Apel). It is, in fact, a road that Dussel himself takes. He builds his Ethics by subsuming Aristotle, Hegel, Kant, Habermas, Apel, Rorty, Walzer, Taylor, among others, and yet, despite the book being published in 1998 there is no subsuming of critical theories of the critical theories; that is, despite being the late 90s, and despite having prominent philosophers like Iris Young (Justice and the Politics of Difference 1990), Seyla Benhabib (Situating the Self 1992),3 Nancy Fraser (Unruly Practices 1989), Kimberlé Crenshaw (Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex 1989), Charles W. Mills (The Racial Contract 1997), etc., who were critical of who Dussel subsumes, he does not include their findings/analysis into his philosophy. I find it hard to think that Dussel did not read these thinkers, and after some searching, these do not appear in Dussel’s work, at least not in a lengthy consideration.

It was after this observation, which I shall call Dussel’s blind eye (to prominent critical thinkers), a question came to my mind. If Dussel’s Ethics are lacking, is it because he only considered the ‘core’? Or, consequently, would Dussel’s Ethics be more comprehensive if they took the enormous post-critical or meta-critical theory? And, as a way of understanding this blind-eye, why did Dussel not engage with these thinkers?

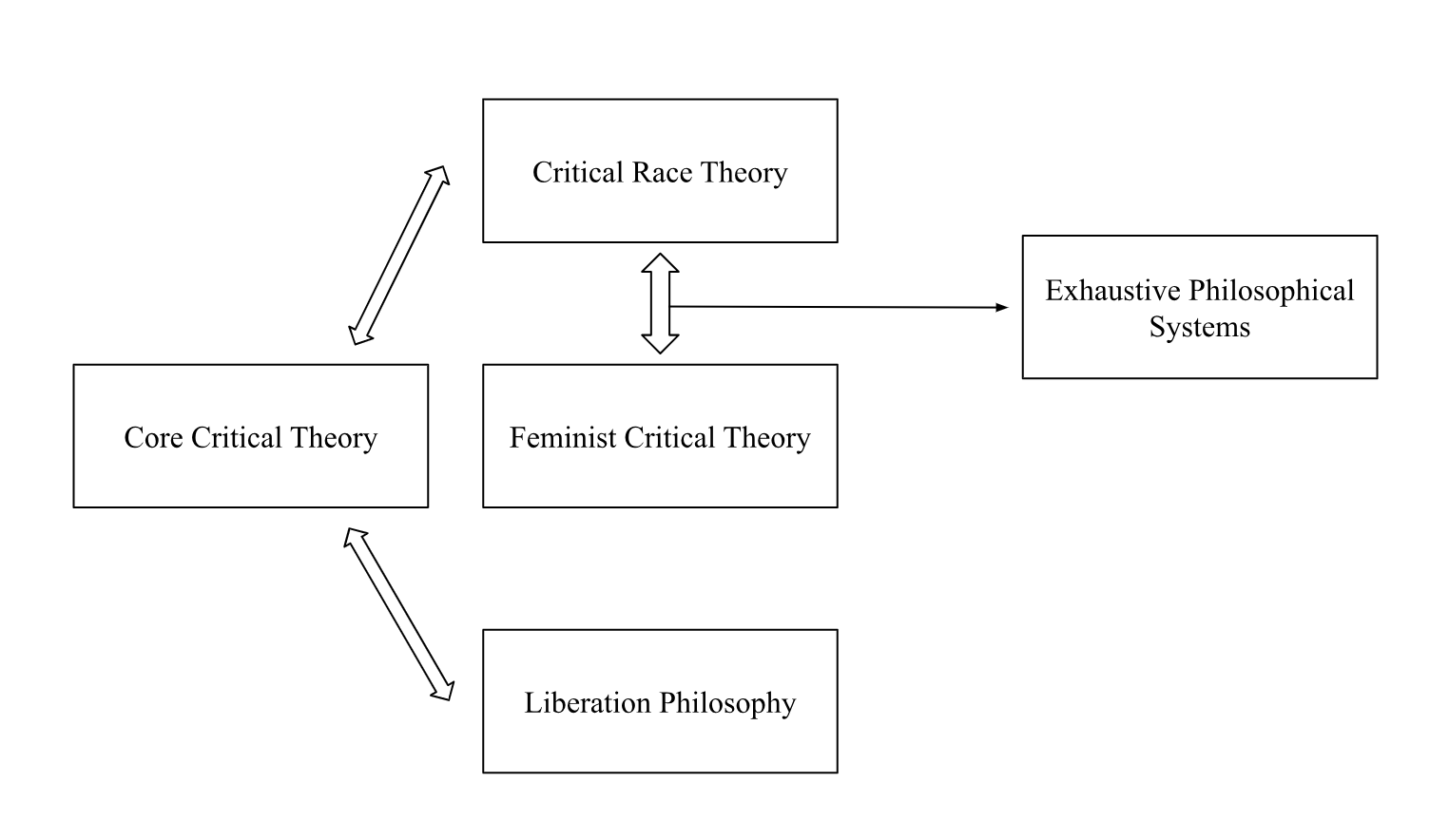

To be absolutely fair, to the best of my knowledge, none of the mentioned thinkers engaged with Dussel’s philosophy or liberation philosophy in general. While liberation philosophy was (academically) battling it out with discourse ethics represented by Apel, on another front was Habermas and Honneth debating the feminist critical theory of that time, and yet, on another front, critical race theory was also engaging a debate. The latter two were situated, of course, in the United States, UK, and continental Europe. It is thus not surprising that discussion between them occurred. One can thus envision the philosophical picture as follows:

Hence, Liberation philosophy was, to some extent or in a certain way, missing from the philosophical debate between feminism and racial theory. Why or how, is a question I do not know the answer to. It can possibly be because of language limitations (although Dussel spoke German, English, Arabic, and Hebrew), geographical limitations, or, possibly, because of Latin American exclusion from academic debates. In general, academia is biased towards Europe (and UK) and the United States. The ‘best’ universities are located in these places, the top journals are also located in these places, and, of course, whoever publishes in those journals comes or studies from those places. Hence, it would not be surprising if Dussel and other liberation philosophers were ‘sidelined’, ignored, or simply, not known. Alas, the result of this unbeknowness is that Dussel’s ethics (and by extension the project of liberation philosophy) is limited. Note that this also results in other systems being limited, but they are not my point of focus.

Disregarding direct interactions, there were feminists and racial critics in Latin America at the time of Dussel’s writings. While, perhaps due to the lingering academic biases these thinkers have not been ‘canonized’ as have been the aforementioned, they have contributed with important concepts, analysis, and systems of thought. These include but are not limited to: Aníbal Quijano, Martha Zapata, Adriana María Arpini, Augusto Salazar Bondy, Francesca Gargallo, etc. Again, Dussel does no exhaustive incorporation or revision to any of these thinkers who had written on the subject of study of specific victims: the racialized and the woman.

Why would Dussel not incorporate such thinkers? Note that this is a preliminary sketch, but I think that the answer lies in what Martha Zapata identifies as one of Dussel’s foundations: “All differences and contradictions are negated by subsuming the subjects of ‘oppression’ under the category of ‘nation’ or ‘oppressed pueblo’ [trans.]”.4 I have written about Dussel’s concept of the pueblo before here. Nonetheless, it is a worthwhile reminder of what Dussel understands by Pueblo. The (1) pueblo originates once “the political community cleaves” from the totality.5 The cleavage (escisión, from Greek: aforismós), being “the oppressed and excluded part, [who] gain creating-presence from a dimension that keeps certain exteriority”, is thus those who were oppressed by the unjust system and gain consciousness of such oppression, and who want to change the totality with an Other.6 That is, the Pueblo are the Other, the people representing the alterity against a totalizing society. Or, the victims. As such, it does not matter what type of affliction or victimhood a concrete subject has suffered from, all types of victimhood are subsumed under the concept of Pueblo. Whether the victim is a poor person, a woman, a member of the LGBTQ+ community, a chronically ill, is absorbed by their status as victims.

The logical consequence is to ask if all victimhoods can be assimilated into a single concept. I have a certain not yet concrete intuition regarding this premise. Dussel claims or pursues a universal ethics, that is, an ethics that is applicable everywhere. Simultaneously, the ethics is differentiated in that it allows for different victims to express their victimhood and thus the necessary changes from their own alterity as per the formal model. And yet, there is only one categorization of the victim (one that I argue is insufficient). It is thus a journey from the universal, to the particular, to the universal. My intuition is that maybe something is lost there. In the transition of a universal ethics, to the situatedness of each victim, to the universalization of the ‘victim’, I sense that at play is a totalizing power. That is, if the ethical problem for Dussel is that victims are excluded from the totalizing system, and seeks to integrate their beings positively by transforming society, but does so by homogenizing all, it seems that the integration aspect totalizes or reifies the victims.

For now, I do not have an actual answer as to how this process happens, if it happens, or if it is an actual intuition. I expect this problem to be treated in the following months by a close reading to Dussel and the thinkers who he has turned a blind eye to.

- Dussel, E. (2011). Ethics of Liberation. In the Age of Globalization and Exclusion, p. 132. ↩︎

- Singer, P. (2009). Speciesism and Moral Status, Metaphilosophy, Vol. 40, No. 3/4. ↩︎

- He does mention Benhabib’s text in a footnote. ↩︎

- Zapata, M. (1997). Filosofía de la liberación y liberación de la mujer: la relación de varones y mujeres en la filosofía ética de Enrique Dussel, Debate Feminista, 16. ↩︎

- Dussel, E. (2015). Filosofías Del Sur. Descolonización y Transmodernismo. Akal, p. 246. ↩︎

- Idem, p. 139. ↩︎

Leave a comment